South Tyrol, an autonomous region in Northeastern Italy where German and Italian languages co-exist, is best known for its spectacular mountain peaks and lush vineyards. Tourists flock to it in increasingly record numbers for its ski and hiking trails, its bike paths and thermal baths, and its food offer that ranges from gourmet pizzas to traditional Knödel.

The diversity of this offer never translated into the media landscape, long dominated by the mighty Athesia publishing house. Still, a variety of voices existed until, little by little, Athesia morphed into a regional monopoly so powerful that, its critics say, is threatening the very essence of democracy: pluralism and freedom of the press. Many in this idyllic region now fear that Athesia’s recent legal action against the small independent news portal Salto.bz is a sign that its intolerance versus any kind of criticisms has reached dangerous levels.

Athesia currently controls about 80% of all regional media and advertising business in Italian and German, both official languages in South Tyrol. It publishes the most important newspapers, operates news portals, radio stations, as well as bookstores in all major towns.

It is joined at the hip with the Südtiroler Volkspartei (SVP, the people’s party), which has ruled South Tyrol since 1945. Athesia’s CEO Michl Ebner (70) has been an SVP politician for most of his life, sitting in the Italian and European Parliaments for a combined 30+ years. He has been president of the local Chamber of Commerce for the past 15 years (and currently running for a fourth term). His brother Toni has been the publisher of the largest-circulation Athesia newspaper, the ubiquitous Dolomiten, since 1995.

Only a handful of non-Athesia media (in whatever form or language) have survived Athesia’s insatiable appetite. One of them is the news portal Salto, which was founded ten years ago by the independent Demos 2.0 cooperative. With its online and bilingual format (journalists and columnists publish in their own language, without translation), Salto clearly caters to an audience that has come to value pluralism not only in terms of languages but also of political, cultural and social views; this readership is open to criticizing a political system which seems impervious to change even as the climate crisis (to name just one topic) questions a local economy largely based on intensive agriculture and over tourism.

The success of the portal, with around 30,000 regular users and subscribers, and the lively conversations in its community and commentary sections, are a testament to its importance as a much-needed space for healthy discussion and open exchange of ideas.

Compared to Athesia’s media empire, its readership remains relatively small. But through unmatched investigative journalism and newsworthy scoops, Salto has also acquired a reputation of fierce independence, as it takes its job as watchdog of the local mighty and powerful seriously. Inevitably, they include the dominant political party and publisher but, for Athesia, this seems to be an intolerable affront.

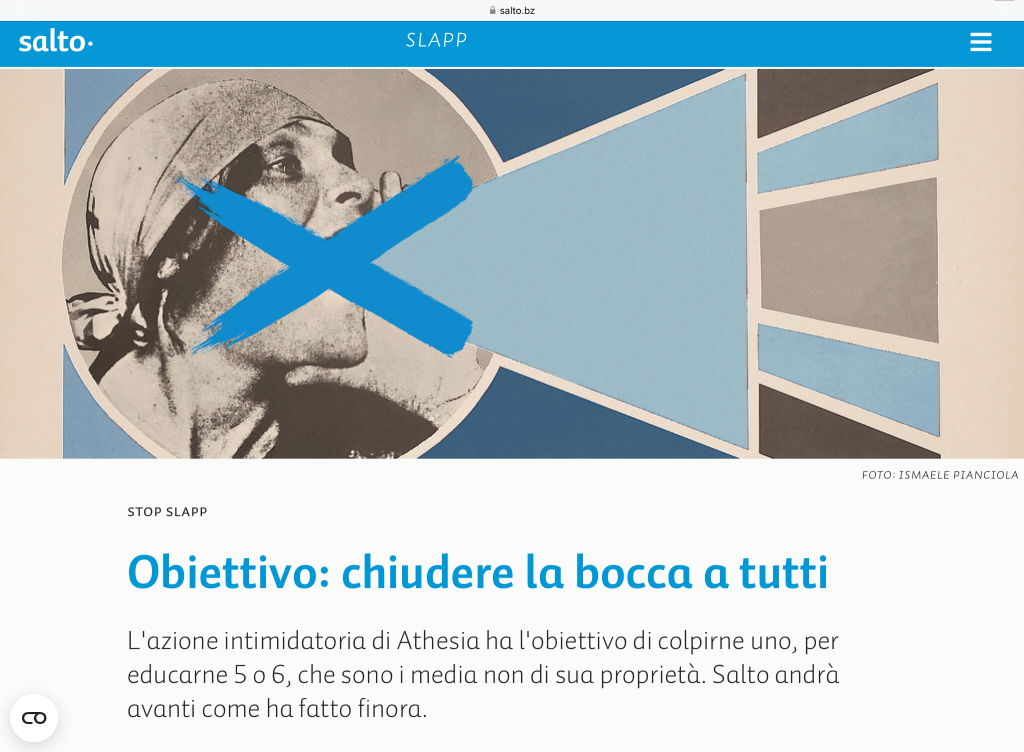

So much so that it has taken the unprecedented step of accusing Salto of “media stalking:” on February 9, 2023, Salto’s publishers were sued by Athesia for alleged defamation. In the claim, which has raised alarm bells throughout the region and has been reported in national and international media, Athesia’s lawyers list 58 articles published on Salto.bz between 2018 and 2022, which, they write, are proof of a “continuous and pressing smear campaign” against the Athesia Group and the Ebner family.

The stories, some of which are opinion pieces, report political and economic events surrounding Athesia, the Chamber of Commerce (chaired by Michl Ebner), and the media monopoly in the Trentino-South Tyrol region. They include interviews with local politicians, journalists or consumer advocates, who look critically at the activities of the Athesia publishing house.

The indictment lists only the titles and publication dates, without any detailed reasons for the alleged misconduct, or any indication of false allegations, misstating of facts etc. The authors of the stories are accused of “media stalking” and the crime of “slanderous insinuations of collusion with political parties and public administration.”

For this alleged “persistent and urgent defamation campaign” Athesia’s lawyers ask for a fine of 150,000 euros, which the publisher intends to donate to charity.

Salto publisher Max Benedikter and editor Fabio Gobbato believe that “the claim for damages is an attempt to prevent the publication of critical news and investigative research.” They also see clear signs of a classic SLAPP lawsuit (strategic lawsuit against public participation) “by which an overbearing media company wants to eliminate an inconvenient competitor. It involves silencing a critical media outlet.”

They vow to “not give up on continuing to carry out, promote and enable independent and critical journalism – the founding principles of Salto.bz.”

While Athesia’s journalists and media outlets continue to offer a deafening silence on the issue, the lawsuit has struck a chord in local civil society, in what seems to be the straw that broke the camel’s back.

An appeal penned by a local historian has now been signed by over 1.200 people, representing concerned citizens, politicians, teachers, students, union representatives, and activists, many of whom believe – or at least hope – that the media giant’s latest action will backfire. As the German newspaper FAZ noted, the fight against the young David did not end well for the giant Goliath.